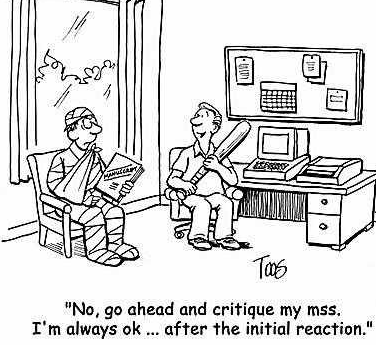

Can Your Novel Survive Editing? Can You?

Can Your Novel Survive Editing? Can You?

Can Your Novel Survive Editing? Can You?

Guest post by Chandler McGrew, author of Crossroads, The Father of the Bride Guide and many other books.

After ten years of writing daily, fourteen finished but unpublished novels, four agents, and over three hundred rejection letters, I was lucky enough to garner my first two book deal. Six figures and with a major publisher no less. My editor was exceedingly well respected and had been with the house an unprecedented twenty-plus years. To add icing to the cake she raved about how much she loved Cold Heart and what an incredibly talented writer I was. It was everything I could do just to keep my swelling head from forming a large crater between my shoulders.

“By the way,” she said, offhandedly. “Could you add a second killer?”

I stammered something unintelligible.

“It would just make the book that much more of a grabber,” she explained. “Let me know when it’s done.”

Therein lies the tale of many a new author’s first experience with professional editors. Since you are reading this, I assume that you are either an aspiring writer hoping to get there or a published author chuckling at her own recollections of the phenomenon. I suspect that many, if not most authors discover after a period of trauma that they actually enjoy the give and take of the editorial process, perfecting their prose until it gleams, brainstorming the plot, learning to add depth and control the theme. Others—some bestselling authors among them—never do accept editorial input, either forging their own way to greater fame or disappearing again into well-earned obscurity by the sweat of their own brows. Either way is open to you, but I must at least give you the benefit of the rest of my story to perhaps aid you in your decision.

I am what is referred to as an organic writer. I do not outline because I can’t stand to know before my characters do where it is that they’re going. But I do edit my own work harshly before ever submitting it to my agent. Unlike most of my novels that take up to six months to draft, Cold Heart was completed in thirty days of flow —manic typing while scene after scene just popped unannounced into my head—and then edited by me for an equal length of time until I was certain it was perfect. But after my initial shock upon having my editor inform me that I had still more work to do on that perfect ms, I settled down (because I had long ago vowed to be one of those authors agents and editors loved to work with) and hammered in a second killer. Voila. Not so hard. Kate, my editor, was going to be surprised at how fast I got the work done.

A week after sending in the revision it came back with a handwritten note informing me in what I felt was a very cold manner that there was more to being an author than just putting words on paper. When I opened the manuscript itself I saw that there was enough blue ink to float a decent sized schooner. I scanned it, then called my agent screaming that I wanted out of the contract, that the editor was writing the book for me, that I could not work with her. My agent listened sympathetically, then informed me that I was very lucky to have received such a large deal for a first novel, that I should suck it up and continue working with Kate on the first two, and that she’d get me a new deal for my next book. I reluctantly listened to her advice, sat down again, and began to type in the handwritten revisions, reading the notes along the way.

When I was finished I resubmitted the manuscript and at the same time sent Kate the largest flower arrangement I could order, informing her that I had learned more about prose and writing in general over the past week than I had been able to teach myself over ten years of arduous writing and studying every self help book I could find. I meant every word of it. When an editor tells you that someone doesn’t have to kneel down, or when you accept the fact that though and although are not synonyms, you have learned something about the difference in someone collaborating on your novel and writing it for you. Cold Heart is not a deep book. It is a murder thriller that takes place over six hours. And the reason it sold was that I had learned the lessons of In Medias Res, internal dialogue, and character development. But I had not comprehended how to polish the entire package until it gleamed, or just how shiny it had to be before it could actually hit the shelves. And I had not seen how much better it could be with Kate’s second killer.

Now, for those of you who are not yet published but have taken the giant step of paying for professional editing of your manuscript, I offer you both my kudos and the following caveat. Revisions suggested by a reputableindependent editor will certainly give you a boost on your way to being published, especially in today’s discriminating market. With each passing year fewer writers will reach that brass ring without first working with an independent editor. But the reality is that one edit (especially by a source outside the publishing house) does not a manuscript make.

To my chagrin Kate informed me immediately after Cold Heart was accepted —part of the editorial process (a book is purchased when the contract is signed, but the final manuscript must be accepted as publishable by the editor before the contract is completed. Some books that are bought and paid for with an advance are never accepted. In most cases the author then owes the publishing house the advance back. See reference above to authors who do not accept editorial suggestion.)—that she was cutting back on her workload, and therefore placing me with another editor who specialized more in my genre. After speaking at length to both editors and to my agent, we agreed that it was a good move all around. Imagine my surprise when Abby, my new editor, informed me that she’d like to see some more changes before she accepted the manuscript.

At that point I had two choices. I could go back to work on the ms (which I thought Kate and I had perfected) or I could have my agent duke it out with the publisher, and we would probably have won, since Kate hadaccepted it and was senior. But having long ago made that vow to myself, I listened to Abby’s comments with a jaundiced ear and went back to work. Once again I was shocked to see that a second editorial opinion had indeed improved the book. More flowers were shipped. By the time we began work on Night Terror, I was prepared for whatever surprises the process held and actually welcomed the challenge. I had also put a line item for flowers in my yearly budget.

My point is that a novel is more than just putting words on paper. It is an amalgam of textured prose, tight plots and subplots, characters that need to speak and act realistically, and a theme that must reveal itself on page one and be consistent all the way to culmination near the final paragraphs and if possible in the last line. For most mere mortals I believe it is next to impossible to hold all that together in one head, to keep in mind all the subtleties in every line, every bit of backstory, unless you are a Tolstoy and work on the same novel for years or decades on end (in which case your chances of being published in today’s market really are thin, but that’s another story). That is where your editor comes in.

So let’s pretend that you have just signed your first contract. In your hands you hold the brown envelope containing your first editorial letter and perhaps the line edited manuscript. Find your favorite reading chair and sit down. Now go ahead, open the package. Don’t be shocked by the blue scrawls, the slashes of lead across lines, paragraphs, or oh, my God, entire pages. Just read (hopefully you have a helpful reference such as The Writer’s Book of Checklists by Writer’s Digest Books that explains copyedit marks), and try to understand what the editor has done in your behalf. Cry as much as you like about that brilliant metaphor that now lies gasping on the cutting room floor.

Then get over it.

Take a day or more to assimilate the fact that the work is better. Then revise it, learn from this one, and go on.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m sure there are terrible editors working in publishing houses who don’t know tight prose from garden trash. I just don’t believe many of them could survive long in a profession where sales are the byword of the day. If an editor made a habit of producing books that were worse when she was done with them instead of better, either she’d have to have Stephen King in her stable, or she’d be looking for new employment so fast the papers on her desk wouldn’t settle until doomsday. Editors work their way up from the bottom (and I mean way below the glass ceiling) by making books better. The worst thing I’ve heard about editors over the past ten years is that they are so overworked today that many can no longer spend the time with authors they would like to or should, meaning that they don’t do enough editing, not too much.

I’ve met authors over the years—every one unpublished—who informed me that some editor had told them that with revisions their work might be publishable. When I evince astonishment that they didn’t leap at the chance to do so, to a man they stare at me as if I’m some sort of troll, and they walk away convinced that I have sold my soul. Maybe. I spent ten years praying that some editor would say those words to me, that I’d get the chance to be edited. And the thing that those authors don’t know, that they’ll never understand, is that I’m a better writer for it.

The trick to surviving the process is to learn what is yours and what is the floor’s. And unfortunately without help, some of the floor’s stuff is always going to remain on the page where it doesn’t belong. No matter how wonderful your story is, it can always be better, whether that requires slashing prose, or adding a subplot to enrich the whole. I know for a fact that every novel out there, every book ever published, for that matter, could still benefit from another editor’s touch. But eventually—because we all are only human—we have to say enough. It’s done. Your editor will tell you the same thing, and if you’re like me, by that time you’ll have come out the other end of the process. Now you’ll be asking her, don’t you think we should change this scene?

Welcome to prepublication jitters.

But that’s yet another story.